~ by Barbara Myers

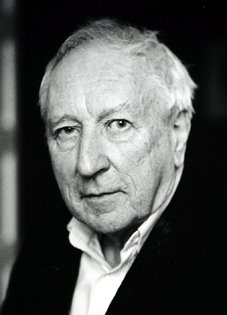

Distinguished Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer, favoured for years by readers, critics and poets worldwide to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, finally took the award this year. He’s 80 years old now and his disciples include Derek Walcott, Seamus Heaney, and Joseph Brodsky, all of whom have won in past years and “wondered why they had got it but not the master.” In announcing his win this year, the judges commented it was “because, through his condensed, translucent images, he gives us fresh access to reality.”

The stars are stamping in their stalls. (“Autumnal Archipelago”)Tranströmer’s work draws on natural, mystical and deeply personal themes, yet as one of his translators, Robin Robertson, observed, “the images leap from the page,” so readers have the sense of having been given something very tangible. The secretary to the Nobel Academy said, “He is writing about the big questions—death, history, memory, nature. Human beings are sort of the prism where all these great entities meet and it makes us important. You can never feel small after reading the poetry of Tomas Tranströmer.”

Born in Stockholm in 1931 and raised by his mother, a teacher, he became a psychologist and worked at an institution for young offenders, while also writing poetry for most of those years. Since suffering a stroke in 1990 that affected his ability to talk, he continues to write and, an avid musician, to play piano with his left hand. The stroke inspired his latest book, The Sorrow Gondola:

All that shines are yellow flowers. I’m carried in my shadow like a violin in its black case (“April and Silence”)Auden was a fan, in particular, of Tranströmer’s prose poems. One of these, “Answers to Letters,” begins, “In the bottom drawer of my desk I found a letter that first arrived twenty-six years ago. A letter in a panic, and it’s still breathing when it arrives a seond time.” This piece includes the wondrous line, “One day I will answer. One day when I am dead and can at last concentrate.”

The bus negotiates the winter night: If it stopped and switched off its lights the world would be deleted. (“Winter’s Code”)As blogger Olivia Olsen writes (in The Huffington Post): “Tranströmer’s world is a strikingly concrete one, inhabited by cars and telephones and silverware. It is also constantly shifting: these objects have the potential to at any time topple into metamorphosis. Each new image is a revelation.”

On the lee side, you can hear the grass growing; …a faint roar of millions of little grass flames… (“Baltics 4”)According to Tranströmer scholar Niklas Schiöler, Tranströmer is the world’s most-translated post-war poet—his work can be read in 60 languages. In English, there are five different translations of some of the poems, including works by Robin Fulton (The Great Enigma. New Collected Poems), Don Coles (For the Living and the Dead) and Robin Robertson (The Deleted World).

Airmail

~ Tomas Tranströmer, trans. Don Coles

Hunting a letterbox

I carried the letter through town.

In the great forest of stone and cement

fluttered this straying butterfly.

The stamp’s flying carpet

the address’s reeling handwriting

plus my sealed-up truth

just now soaring over the sea.

The Atlantic’s creeping silver.

Cloudbanks. The fishing boat

like a spat-out olive-stone.

And the keel-water’s pale scar.

Down here the work goes slowly.

I often sneak a look at the clock.

Tree-shadows are dark figures

in the greedy silence.

The truth is there on the ground

but nobody dares take it.

The truth lies on the street.

Nobody makes it his own.

from For the Living and the Dead, Buschek Books, 1996. Reprinted by permission.

Barbara Myers‘s work was recently included in the Montreal International Poetry Prize shortlist Global Anthology (Vehicule Press). Whistle For Jellyfish (Bookland Press), of which she is one of the co-authors, has just been released.

Award-winning writer Don Coles has published ten books of poetry. His translation work has notably earned him the John Glassco Prize.