I was eighteen. I wasn’t writing yet; I was thinking about it. In a black notebook with stickers on the cover, I set about filling the pages with quotes from poems I loved fervently. I picked these from poems in the books I found in the stacks at the Ralph Pickard Bell Library in Sackville, New Brunswick. Have I ever been as quietly and industriously seeking something as I was back then? I chose linen spines I liked; lonely for words that described me and my feelings, lonely for someone else’s description of what was inside me. I slid out a book, I opened it to any page. I hoped for a reprieve and I found it.

Like most teenagers (most people?) I felt incongruous and more than a little lost: inside myself I was one way: a freckled girl without many friends, walking past silent carrels, reaching out to the books, feeling wondrous, careful, sensitive. Outside of my spot in Ralph Pickard Bell, I loved people and things a little too strongly. I blurted. I was cavaliere, witty. I hurt others impulsively and felt terrible almost always. I must be crazy, I thought. It still confuses me, how I appeared to the world, how I really felt, how I seesawed between states of emotion, both inside and outside myself.

In the stacks, I felt safer. The dusty mushroomy smells of each book spine I cracked, the deep turquoise carpet I sprawled on in oversized Levis, army boots and work socks, my feet slowly going to pins and needles. When I could stand it no longer, I slumped over the railing of the rotunda, shaking my feet to bring them back to life. Below me was the marble circulation desk, the wooden wall of card catalogues I never bothered with. Below was the turnstile clicking, at the entrance, and look: my crush’s coming through it, backpack over one shoulder. Who would have the guts to call out to him? Not me. I returned to my search for my feelings. I returned to a poem for some courage. And I wrote it down in my journal.

In finding poets who spoke to me of feelings, I felt less lonely and more defined. Writing down quotes (and citing them of course) defined who I was, and who I am:

you feel like me. And I you.

I have a terrible memory. This is a failing. It’s embarrassing. I can’t remember the lines or words that I needed at eighteen. No doubt there was Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton. No doubt there was Galway Kinnell—sexy!—and Alden Nowlan—not sexy, but man, his imperfections were my imperfections and somehow he could forgive me mine at least.

But it is you I really want to help out here. For your sake, I went back to the books, so you can trust the quotes to be relatively accurate. I don’t want to mangle these important precise words. Many I’ve had for a long time, tacked and retacked to the cork above my desk. Some I’ve found recently in this COVID time.

So, if I was you, I’d tell myself to seek out the strange, alienated speaker at the beginning to Dorothy Lasky’s Ars Poetica:

I wanted to tell the veterinary assistant about the cat video Jason sent me

But I resisted for fear she’d think it strange

I am very lonely

Or whoa, this haunty bit from Elizabeth Barrett Browning:

But I could not hide

My quickening inner life from those at watch.

They saw a light at the window now and then,

They had not set there. Who had set it there?

I mean—the wonder here, right?

Or Susan Gillis, from Obelisk 12:

My old friend says he doesn’t remember the thing I’m finally

apologising for.

it’s meant as a form of kindness.

But it makes me furious.

I know the feelings in the lines above because they are my feelings. And so the poets are my poets. I keep their words, imperfectly remembered, inside me. In Ellen Bass’s poem, What Did I Love, the speaker argues for the beauty of butchering chickens. She compares innards of a Cornish hen to human wonder:

Over and over, my hands explore

each cave, learning to see with my fingertips. Like a traveller

in a foreign country, entering church after church.

If Bass isn’t saying I have seen it (Elizabeth Bishop’s so-called directive about how necessary imagery is to poetics) I don’t know what she’s saying. And I feel it.

These COVID days, as I try to keep upbeat in my online teaching, I repeat: The arcades sell postcards of old photographs of the arcades. It’s from Stephanie Bolster’s The Invention of Distraction. I watch my students watch me (and themselves) on the screen. (I imagine, hopefully, that they press replay so they can re-watch my lecture later, when they are alone and can pay better attention to the message. Maybe. Maybe I have an effect and so I am less alone?)

I do love mirroring in poetry and how it asks a kind of empathy, no? Take this example, from Hieu Mihn Nguyen’s Changeling in which he describes his mother standing in front of a mirror:

I watch her pull at her body & it is mine. I tell my mother she is still beautiful and she laughs.

The room fills with flies.

These flies are heartbreaking, familiar: it’s the struggle between mother and child: my mother and me, my child and me. Maybe it’s your struggle too.

In Susan Elmslie’s Seven letters to my mother, she asks her mother for forgiveness for stealing earrings and then breaking one:

I still have it

the black diamond loose in my own chest, for shame. A hopeless case.

But she is not a hopeless case! And so neither are we.

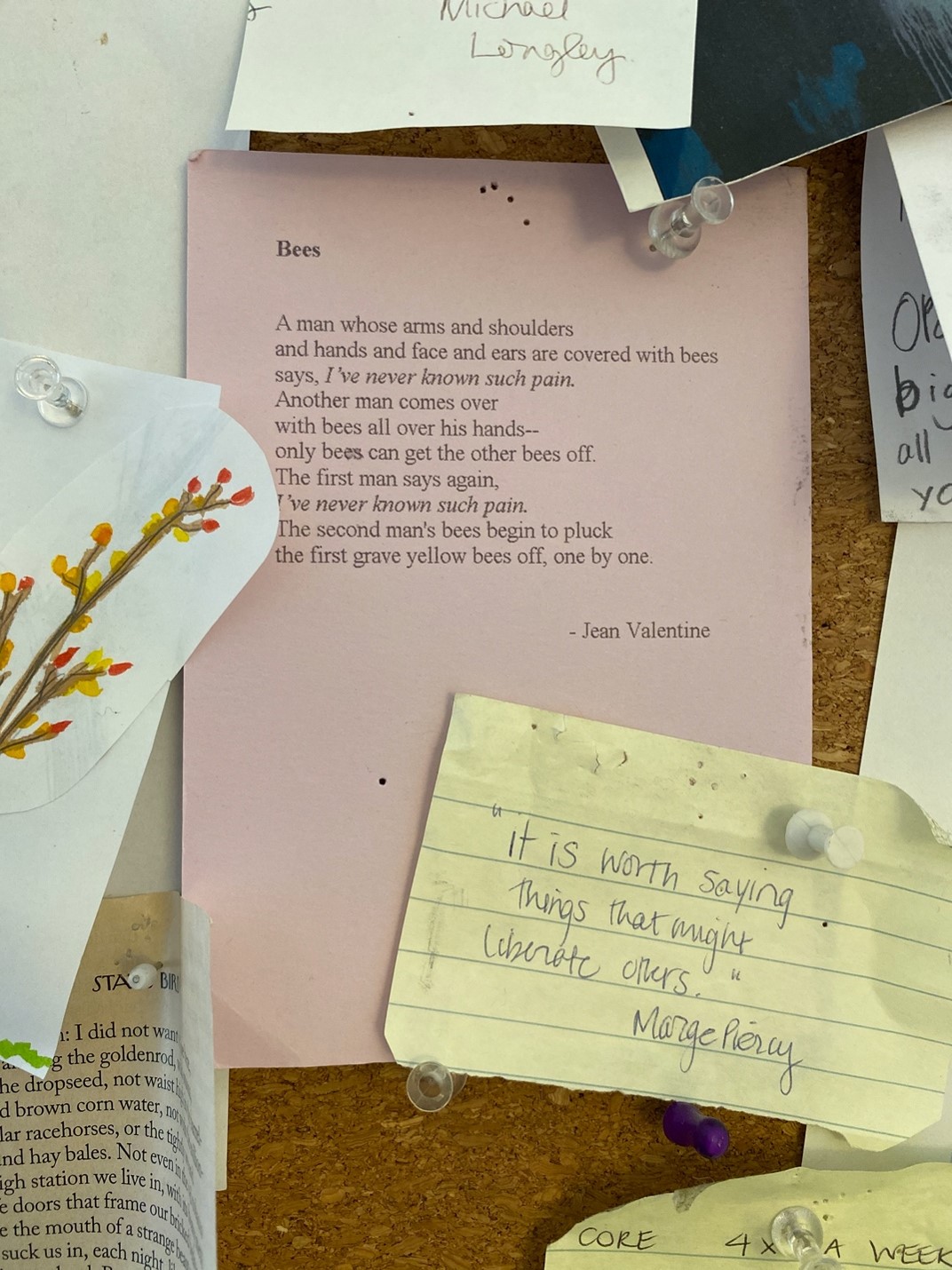

You must know as I know Bees by Jean Valentine. I have it here, typed on lilac cardstock pocked with tack holes and ragged from my attention:

A man whose arms and shoulders

and hands and face and ears are covered with bees

says, I’ve never known such pain.

Another man comes over

with bees all over his hands –

only bees can get the other bees off.

The first man says again,

I’ve never known such pain.

The second man’s bees begin to pluck

the first grave yellow bees off, one by one.

Valentine’s interjection explains both what we need to suspend in her poetic dream and what we need to believe: only bees can get the other bees off. It is true: only those who have felt what you’ve felt can heal you. I’d like for my eighteen-year-old self to hear this. I don’t care about her oversized Levi’s, or her feet going to needles again on the carpet. I just want to make sure she keeps reading and writing. That crush, with his backpack can’t heal shit for her. What can heal her is this moment, coming up in her life. She’s at the Atwater Library waiting for some poets to read. She doesn’t know any of them. But then Sue Sinclair is introduced. And Sinclair takes the mic and begins to read a poem, Surrender:

Sometimes the light, a horse,

gallops into the room

and demands you surrender.

[…] Your only choice

when the world lifts its head

and clarity pours from its back.

Filling the room.

I’ll never forget that moment—not the words, but the feeling of being in a church then. Exalted, maybe. And I remember the ache in my chest when I first read Susan Elmslie’s Miracle, in which her speaker and her child go to a doctor’s appointment. The doctor is a heartless clinician. After a brutal and cold diagnosis of her child’s condition, the speaker, who is a teacher, tells us she could do nothing but say goodbye to the doctor and run back to her classroom:

arriving dazed, rain-splattered, in my coat, to teach the assigned poem,

“Pied Beauty.” Reading Hopkins aloud

to fresh, unworldly faces,

this time,

when I got to All things counter,

original, spare, strange, the skin of my life caught in the teeth of the poem

and it sang through me.

What am I saying here? I guess only this: right now is no easy time. But if you can disengage from the news and the numbers, detach from the gossip and the crushes and the buzzfeeds, if you take a step into your own spot, and leaf through the books to pause only when a word on the page takes your attention, I promise you, poems won’t mistake you for someone you’re not. They’ll not miss the point. Poets are our people. They vindicate our innermost feelings. They understand you and your feelings in this time you are in. In this hard time we are all in together. That crush with his backpack? Not so much.

Sarah Venart is the author of I Am the Big Heart and Woodshedding. This past year, her work was published in The Moth (UK), So to Speak (US), The Malahat Review, and Concrete and River and on the longlist for the Frontier Poetry Industry Award. She lives in Montreal.