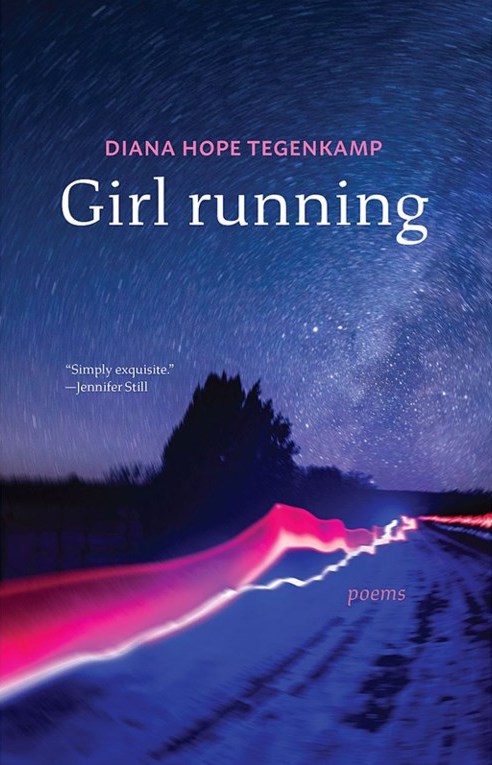

Diana Hope Tegenkamp’s debut poetry collection, Girl running from Thistledown Press (2021), invites the reader to experience the dream as a lens, an idea, and a word for a complete state: across parts of speech, verb, noun, and adjective. Personal and political, the poems are thematically interwoven with intimacy, family, and history. The poems also explore grief, where the past and present meet and extend across the speaker’s waking and unconscious minds, as “[s]mall gestures from dreams / materialize in the day (untitled epigraph).” The reader finds poems traversing this gradient of consciousness.

As a mixed-media artist, Tegenkamp translates for the eye. Her imagistic use of language, at times, moves ahead of meaning into interesting and experimental spaces. In the poem, “Frequency,” the speaker asks, “What about so much light / the mind goes white?” In “Little Winters,” a suite of poems in which winter is both the season and a central conceit for the speaker, her “… mother / opens the front door // snowflakes floating round her / profound as secrets.” The piece also carries references to the artist Fujiko Nakaya, an artist renowned for her sculptures and installations, who is “in love with snowflakes.” And Tegenkamp works with the concept of poems as installations, seemingly influenced by poet Nicole Brossard. A reader might find they are walking through the white space, in the experience of the poem, surrounded by curated fragments of image, memory, and perception.

This collection also contains a feminist critique of history and many poems that interrogate the enormity of societal injustices, specifically Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG). Equally evocative pieces bring a focus to the level of the family and the self. In the section entitled “Arterial,” these distinctions blur as history, grief, and family are enmeshed with the poet’s own Métis identity. An untitled epigraph frames this complexity, which seems to defy delineation, as a “… junction you / never found / perspective with no end.” With the poem “Birthmarked,” the speaker conjures a dream-like scene of tragic tenderness, suffering, and love, alluding to the Sixties Scoop that imagines the speaker’s father and grandmother reunited in heartbreaking embrace as the “treeline edge / forms and re-forms within him.”

Continuing to look at these larger societal injustices, “my | BELOVED | HISTORY” employs strong visual elements: the photographic reproduction of a historical text distorted and struck-through, the primary text dwindling until all history is a footnote. Referencing Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) as parenthetical “(sometimes) (found) (or not) (later) (summed|up) / (as acronyms),” the poet goes even further until even the footnotes are redacted. History is hidden or else revealed by its multiple distortions.

Grief and loss, the thread that runs throughout this collection, find culmination in the final poems of the book, “Naming” and “Motherfield.” In “Naming,” a poem in seven parts, the speaker chronicles the final days with her mother. Tegenkamp offers palliative scenes with sparse dialogue of description, ineffably and emotionally stirring. The poem is a way of naming, expressing with a mimetic quality, these hardest journal entries as “something beyond/ sadness, some wordless thing.”

Bios

Michael Edwards

Michael Edwards lives and writes on the traditional and unceded lands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqeam) people (Vancouver, BC). He is editor of Red Alder Review and a graduate of The Writer’s Studio at Simon Fraser University. His work can be found in various literary journals. [updated in 2022]