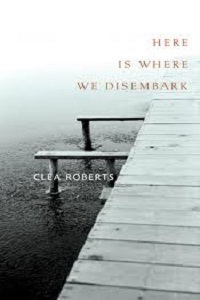

Clea Roberts. Here is Where We Disembark. Calgary: Freehand Books, 2010.

~Reviewed by Brenda Leifso

Before getting too deep into this review of Clea Roberts’s superb Here is Where We Disembark, I’d like to just bury all the assumptions about “Here We Go Again, More Enchanted Canadian Writing About Wilderness and Place” under a nice big boulder in said wilderness and keep them there for awhile—or always. True, Roberts does write out of the Yukon (an underrepresented territory itself in Canada’s “place” writing), but to shelve the book neatly in a category that is itself problematic would be to do Roberts a great disservice. While the Yukon’s wildness may provide the poems’ foundations, their walls are constructed from human relationships, from disaster averted, and from the greater question of what it is to build or lose a life in this complex world. The poems reflect this complexity in deceptively simple lines. Consider “Cathedral”:

and that is almost what we believed

in heaven and all its permutations

as you fiddled dog biscuit, house key—

the artifacts of the known world

in your pocket.

Or, “Weight,” in which the speaker finds a woman near-freezing on a trail:

the recognition I made a hair appointment

then took an early lunch

before my walk in the woods.

That’s all it took

to become a deciding factor.

She is not the hero,

I am not the hero.

Another of the book’s strengths is its ever-present, quiet humour. In “A House is Built,” Roberts “dream[s] of wooing / drywallers. / Strong, honest men who answer their cell phones.” In “Rendezvous,” she doesn’t “need / a hairy leg contest / to tell me it’s been a long winter.” At times, the poems (“Lure,” “Caption”) in the second half of the book—Gold-Rush era imaginings from characters’ points of view—don’t sidestep the obvious as well as they do in the book’s first half. I’m also not entirely convinced that this section—30 pages to the first section’s 70—is balanced with the rest of the book. These are quibbles, though—the book still holds tremendous power. Despite their unassuming nature, Roberts’ images are lonely and exact. In “Longest Night,” the moon

fills

the snow tracks

of tree squirrels

with blue shadow

level as teaspoons.

In “Nature of Nature,” Roberts watches how

even in sleep … an earnest dog—paws that twitch

at dream velocities

and the tight, deep howls

and silly whimpers,

the tuning and retuning

of the instrument of longing.

In this book, you will find wilderness in its softer forms, yes, but you will also find hunger and

hunger stills finds you:

a flurry of paw prints, wing tips,

entrails radiate, the violent flower

of skin and bone.

Brenda Leifso’s next book of poetry is coming out with Pedlar Press in Spring 2015.