Working at the knot of settler guilt and regional identity, Laurie Graham explores the creation and maintenance of inherited and local memory in Rove, her book-length long poem debut. Swiftly moving, self-assured, plainspoken, loose, funny, and pressing in its occupations, this is a book you read cover to cover in one sitting. And then you read it again. It’s hard to believe this is a first book, so whole, so wholly realized, this persistent, generations-long tracking of a single family and their place. With sustained attention and a deeply intimate, yet hospitable lyric, Graham takes us in, introduces us to the folks, their Ukrainian-Canadian roots and language,

living on homesteads around Angle Lake and Meadow,

sitting around the table Saturdays before or after the dance,

cigarettes and brown beerbottles

…and the ability to laugh.

The book opens with an incantation to the place, given in couplets, in a wry, energetic vernacular, its loyalties both private and public:

Say the laundry on the line, say the dank root cellar,

say the numbers, tell the Wheat Board where to go,

…say Ralph Klein and spit in the dirt.

Say Skye Dancer, say Zwicky. Say Alberta and Saskatchewan

and switch the order. Say Wayne Gretzky Drive,

say it’s five-on-three and he’s on a breakaway,

…say your little heartbeat, send it through the layers,

say it in the muck in this marsh, in this bristling parking lot.

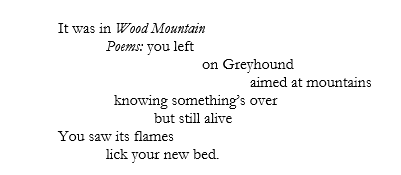

When the family farm is then lost to the suburb (in this case, Sherwood Park, Alberta), Graham aims her images at the politics of such contrasts, invoking the old néhiyawak (Cree) names against the modern realities of a robust petrochemical industry and “the grass green bed of the suburb in windshot / of Refinery Row.” Acknowledging her poetic inheritance from another prairie voice of Ukrainian descent, Graham addresses lines to Andrew Suknaski:

We hear, then, the speaker’s apprehension of her project’s immensity: How to make a home on colonial territory?

Despite a propensity for humour throughout, there is real sorrow here, the migrant’s agony of displacement, passed on to a next generation who gets it perhaps even worse—the unnameable ache for a place she has never known:

Three pencilled names on a torn page

in my mother’s jewel box: Bolishi, Moatiski, Drogowich.

Not sure where these are

but I’m from there in part.

As the speaker grows up and “roves” between her native town and other Canadian cities, she wrestles with location, “across phone lines,” quitting and returning to a place “all changed now.” We are pulled along with her, into the web of family relationships: “the grief of mothers and daughters”; a father’s “laugh like all the laughs I’ve heard”; “the old grocery store / where all the cashiers knew Grandpa’s name”; to a “home calling like a horn through fog.” It is well worth the travel.

Danielle Janess‘ poetry, interviews, reviews, and translations have appeared in journals such as Poetry London (UK), Event, CV2, Prairie Fire, and The Malahat Review. Recently an editor for Sand Journal and CWILA, she is currently an MFA student fellow in the Department of Writing at the University of Victoria.

TAKE ARC WITH YOU, WHEREVER YOU MAY ROVE.