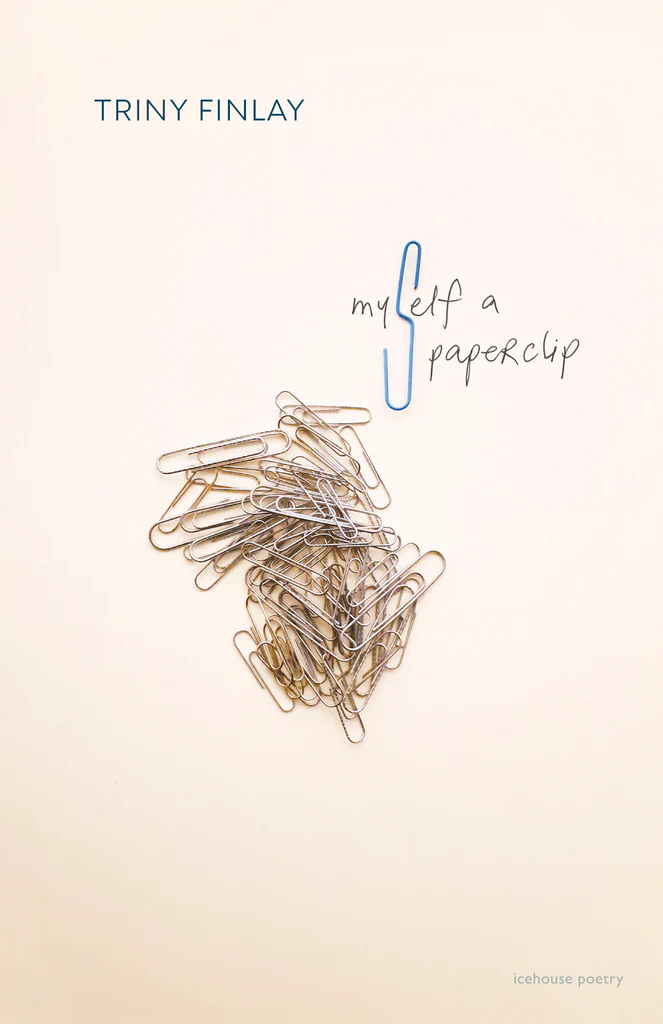

How do you incorporate the essence of your poetic forebears to heighten a new work without intruding on contemporary narratives? This question is answered eloquently in Triny Finlay’s new collection of poems, Myself a Paperclip. Finlay captures the stigma of mental illness and its treatment in her own words with the support of allusions that provide the reader other texts that fill out the psychological grounding/tradition of the narrator.

Myself a Paperclip riffs on T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” throughout, playing with the idea of the metaphorical patient etherized upon the table, its narrator uncomfortable in their own skin. But Prufrock is not alone. Finlay’s text starts with the line: “In the room, the women come and go, talking of the elusive O” (untitled poem). Based on the next few poems, this references The Story of O, the erotic novel by Anne Declos (AKA Pauline Réage) that chronicles the dominance and submission of its title character.

The narrator does not seem powerless in Finlay’s poems, though. Poems like “#MeToo, and You, and You, and You, Too” and “Adjusting the Psychotropics” seem an antidote to O’s suggestion (and that of society’s, by extension) that the submissive female is a kind of ideal. Here in Finlay’s work, we have a strong narrator ready to name abuse for what it is and reclaim its narrative.

There’s more intertext in Myself a Paperclip, notable in another untitled poem when Finlay conjures Sylvia Plath in reference to a phone ringing: “It jars. It jars. The bell jars.” The Bell Jar is, of course, Plath’s one novel, seen as a thinly disguised memoir of her own treatment for mental illness. The poem is a very direct allusion to someone whose illness and death has been examined ad nauseum through her works, an unavoidable weight for anyone writing about mental illness. Finlay doesn’t belabour the point, just reminds readers that Plath is never distant for the modern writer. She is an inevitable sliver in a differently complex narrator.

Prufrock looms largest, of course. Reading and re-reading both texts, they become something more reflected upon each other. It’s in riffing on Prufrock that Finlay is sometimes at her funniest, as in another untitled poem: “I grow old… / I grow old… / Olanzapine + peanut butter toast + zippers in pulled polyester / give me psych-ward camel toe.”

Much of Myself a Paperclip is situated in a psych ward. Finlay captures the various personalities present in that space via overheard conversations and descriptions of “types.” Amid this, Eliot’s words are bled of their fanciful nature to speak of a very real existence: “Afternoons and evenings, rigid and asleep, / I have measured out my life in plastic cutlery” (Untitled poem).

Finlay manages to have us see Eliot’s metaphoric etherized patient while also presenting an actual patient struggling to wake and not so much conquer their illness but tend it with care and awareness: “I know they’re here / when the guitar strings whistle / across my bedroom. / A whisper of wind tells me / it’s time to go” (“Where I Meet My Diagnoses In the Real World”).

Again there is an echo of Prufrock in the final line but also a realistic understanding of self-care. And that’s where the two texts seem to diverge. Where Eliot’s character seems paralyzed with indecision, Finlay’s narrator seems determined to push forward. They are tired but determined not to drown. That, sometimes, needs to be enough.

Bios

Robert Colman

Robert Colman is a Newmarket, Ont.-based writer and editor. His most recent book of poems is Democratically Applied Machine (Palimpsest Press 2020). [updated in 2022]