2009GGs offer dazzle vs. wisdom

Feature Review

~ Patricia Keeney

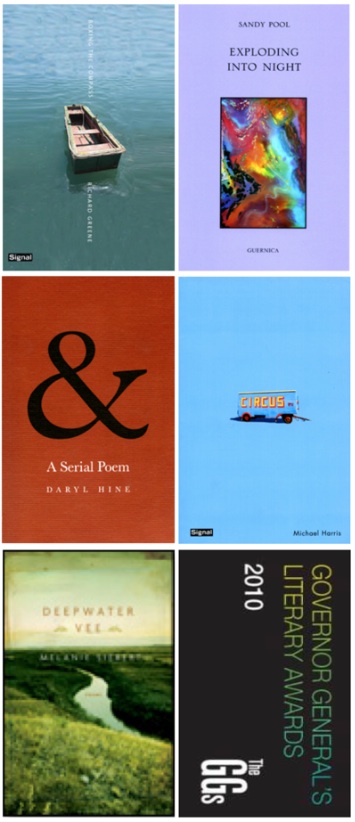

Richard Greene. Boxing the Compass. Montreal: Signal Editions, 2009

Michael Harris. Circus. Montreal: Signal Editions, 2010

Daryl Hine. &: A Serial Poem. Markham: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 2010

Melanie Siebert. Deepwater Vee. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2010

Sandy Pool. Exploding into Night. Toronto: Guernica, 2009

The 2010 contenders for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Poetry share the recognition of nomination. All deserve to be there. But who has been left out? Does the fact that they are all GG contenders pre-dispose me favourably towards them or make me sceptical? Critical objectivity is always an issue, for reviewers and juries alike. It should also be acknowledged, though, that some subjectivity is both inevitable and desirable. As competitors, these books have already been deemed worthy by others. This means either that a level of my job has been done for me or that I must assess the collections even more rigorously. I find it works both ways.

The most interesting differences among these poets revolve around a generational divide. The younger poets here, with their dazzle and verve, seem to invent life, revel in its newness. The older, seasoned poets distil life, sift and sieve their experience through their words. That first-time thrill is gone but the wisdom is there, the enriched sense of having earned the attitudes, perceptions and compulsions that drive the work.

This is true of Richard Greene’s collection, Boxing the Compass, which travels cityscapes with the dispossessed, Newfoundland’s stormy history and the seedier bus and train routes of America. His voice is meditative and searching, mixing the elegant with the colloquial. It is an inclusive voice that, nonetheless, seems unable to find what it is looking for, whether in urban environments with their moments of metaphysical enlightenment amidst decay, in churches that have lost God but still manage minor salvations, in students who will eventually find poetry, or the sea-salty whaling memories of the narrator’s father’s time, hardening into myth. Technically accomplished, the poems are uniformly paced and assured, telling their stories easily, conversationally. Greene takes readers to his people and his places assuming that they want to accompany him, because we are all spiritual wanderers, and every age is poised to hear the still sad music of humanity.

The priestly poet or the poet-priest incarnation is one that distinguishes this book. Greene spends much time contemplating churches. The association of poetry with the divine is not new; it reaches to classical times. However, Greene’s contemporary voice is a non-egoistic one that seeks tirelessly and admits failure: “It was a thing I almost wanted- / priest of the Church of England, as I had failed to become one in the Church of Rome.” He is “bound by that imagined self / I could neither inhabit nor escape” and can barely separate desire from mourning, his dilemma imaged “in the shadow of a hill thrown forward / onto level ground, the illusion of ascent.” It is a careful image full of personal indecision and resonating with ecclesiastical history, containing the sort of quiet power typical of Greene’s best work. By contrast, some finely crafted poems on the Christian theme—“Two Chronicles,” “St. Ignace”—enjoy holy martyrdom a moment too long.

Greene frames states of mind and heart with a characteristic subtlety of sound and the mysterious suggestion of forces working towards something. There are small miraculous moments: “At morning love stirs… shakes the night’s snows from its limbs, / sees an unbearable light / refracted in icicles.” And occasionally unexpected wonder: “Love is a conversation in a water-drop.” There are perfect lyrics that say it all so simply. “House and Barn” begins with the weight of winter and ends looking “into miles of fog,” not knowing “what weather passed for dreams/ in a bed where my first years grew cold.”

Deliberately more lax and casual, Greene’s Over the Border sequence features rhythmically paced conversations with odd characters in cheap American hotel rooms where he must “kill time” between archival forays.

The most vigorous poems in the book—whether muscled recreations, sharp yearnings or some compulsive existential search—embrace Newfoundland. It is “the stark coastland of a question” and, “I am always here,” claims “Utopia.” With the opening lines of “Whaler,” one is in Robert Lowell territory. But Greene quickly individualizes his own ancestry: “Great-grandfather, whaler out of Nantucket… / Grew old jigging cod…” and continues, later in the poem:

What I have of him

is my father’s reverence for

his silence, a sense that pain will kill you

if you speak of it.

Greene’s title poem “Boxing the Compass” aches with memory, seethes with desire. He dives back, watching whales as a boy when he “could not tell a pothead from a wave.” Sleeping “at home” years later “I lie through a night of gales / in your emptied house and see them pass, / blow, plunge in waters deeper than a grave.” With their deft handling of narrative and vivid vignette, these fond memories, though occasionally predictable, embrace a wide humanity often caught in a Heaney-esque turn of phrase: “A boy’s shape vanishes into the man’s form, / tramping after you my lifetime ago.”

*

Michael Harris, another veteran of the trade, has produced in Circus an energetic high-wire act that runs on the adrenalin of reforming zeal and the comic anger of satire. There is an irritated spirit behind this performance, impatient, self-mocking, role-playing. The voice is consistently “on,” aware of audience, the circus itself being an obvious analogue for life and art or even a life of art. What happens under the big tent, “our temple of canvas and straw” is by turns exciting, giddy, nasty and touching. The poems are actors, existing for their audience. They want to amuse, upset, manipulate. In a refreshing take on perspective, Weary Willy, the sideways man who makes “homo horizontal” the norm and takes three hours to walk across the tent floor is “just trying to slow things down / so it’s the circus going round, / not me.”

Easy but nonetheless unexpected segues land us from circus to life and back again with dizzying, not to say dazzling, dexterity. In the poem “Custodian,” the anonymous central figure has morphed from “pen and podium” to “mop and bucket, shovel and broom.” He develops crushes on the trapeze artist, relationships with the animals and an intimate knowledge of troupe gossip such as who “is schtupping the make-up girl.” As the garbage man, he is also archaeologist, anthropologist, psychologist and, notably, apologist. Behind all these incarnations lurks the poet, from Will through Emily to Ted, without whom this writer/garbologist would be “teaching grammar somewhere / Editing texts.” Effortlessly navigating literary allusions, Harris glides his readers to the custodian’s “last class as a College teacher” (full of hilariously naive students) and concludes both philosophically and lyrically that “few want the job as janitor. / O once I sang in my chains like the sea. / Now, thank God, / I’m free.”

Harris is a quick-change artist. He slips in and out of masks, appears and disappears between what is apparent and what is real, what is said and what isn’t. The manic performer adroitly lets his disguise slip in “Concentrate.” Dusk creeps across the provincial wilderness while “the wire is set and the rigging steady.” In the next line “there should be little to make you hesitate but a want of confidence // unless you were to slip into musing about the various malaises of domesticity…” Despite such distractions as sex, one must “move on” knowing that “The crossing itself is an act / of balance.” The poem snickers about how awful a fall would be, considering “the roof guaranteed for ten years, the car just oiled—all gone / in the middle of whatever wildlife may have engaged your interest.” With that last reference, Harris returns us to the poem’s beginning in crepuscular Canada with its raccoons and moose. “Concentrate” is a typically virtuoso performance.

Like any worthy satirist, Harris occasionally just pulls out the stops and enjoys the show, warts and all. “Ringmaster” is a singsong rhyming romp through such items as “The girl on the pony with jiggly bits. / The loaves of manure the elephant shits.” While the compulsion to entertain and divert can be wearing, Harris executes his turns with aplomb. Smooth structures and sure, complex syntax pull together language that serves each scene: the jangly juxtapositions of Molivos, chewy words in James Joyce, the lovely “ring of shuffling penguins / revolving shoulder-to-shoulder slowly through the months” that cause Ormsby of Antarctica, on the lit deck of his ship, to lift his wings and join them. Even though the circus cannot avoid the “house of horrors” that is history, “fuller than the bag full of ears, / the ditch full of Jews,” it can marvel at lesser things: “a vulture folding the umbrella of his thin shadow up / over some fluttering rag of skin on the ground,” observations that allow this poet the free-range lyricism needed to enrich his disenchantment. When the balance is right, one is both impressed and moved by Circus; when not, one is still impressed.

*

Daryl Hine, also a poetic past master, writes the astonishing &: A Serial Poem. The book is an almost manically maintained tour de force of 303 10-line poems “linked by and flowing through the ampersand,” or the inevitable onward chug of life, sure as time and night, sunrise and death. Alternately spiritual biography, artistic biography, the documentation of an art form, the tracing of a love life, the gleeful/glum confessions of a language addict, & urges you forward on a thrilling trip through puzzles and pure thought, the homely or wondrous details of the quotidian and the sublime silliness of mucking around in the word horde.

Hine’s syntax alone is a trip. Many poems play hide-and-seek with the subject. His enjambments are often ingenious:

Nothing if not an indispensable envelope

For memorabilia, amused

By nothing, a medium to be used,

Spent or wasted like a bar of soap

That will outlast us, or an endless rope,

A gratuity that cannot be refused

Unlike such synchronicities as rhyme,

Time passes away, sometimes a slope

We scramble down, disheveled & confused,

Sometimes a winding stair up which we climb.

With the basics of form and technique so firmly in place, Hine can play freely, conveying idea, emotion and wit through the images and resonating patterns they seem to inspire. & begs to be carried around like a pocket Shakespearean Sonnets, dipped into and savoured in delicious bite-sized morsels.

In a Hine poem, sound and sense work seamlessly together. In a naturally ironic language that thrums with literary, philosophical and colloquial allusions, Hine wanders over a range of pain, time, memory, weathers, the soul, the afterlife, home, poem-making, age, love, despair, days of the week, the writer’s tyrannous diary (which sometimes oversleeps) and dawn, where he spends much creative energy: “Yesterday the sun came up again / After an excruciating night, / To scour with indiscriminate appetite / The grown-up mountains and pubescent plain…”

In Hine’s world, the moon, “that ghastly ghost,” can be amusingly inferior and language “a hydra-headed fountain” that he spends pages teasing and criticizing. Stumbling dizzily through poetry’s formal demands towards Eliot and Nietzsche, Hine heads “Down a strophic staircase” into “a stanzaic waiting room” where “Staggered sentences stumble to resume / A scheme to unwind inevitable-seeming / Verses & reverses eternally returning.” He follows Narcissus in his “auto-intoxication” through which “an elementary school / Of minnows flickered” to where “The looking-glass glistened, / Enraptured at having captivated a natural fool / Who fell for himself.” Elsewhere, the mind occupies Hine; if you have lost it, why bother looking for it? A sandcastle “abandoned on the shore, / … It lies in ruins though the site is haunted.”

Not all the poems open up; some close in upon themselves and occasionally a semantic knot refuses to loosen into real comprehension. Every so often, an ending will turn self-indulgently pun-ward, weakening the impact of the whole; alternatively, the language simply falls off. At a hundred pages plus, there is a slight sense of repetition (but of course, life’s like that).

These are minor quibbles compared to the intellectual and aesthetic pleasures found, the hard-won affirmation contained in the lines: “Cherish, so long as there is time to cherish / The present tense until it shall have passed.”

Hine draws a detailed map of life both lived and imagined, of the cost exacted and the knowledge gained. No position in his serial poem is fixed or finished or absolute. Indeed no positions are taken. Gestures are made. When you close the book, you don’t close the process. As the ampersand itself insists, it all goes on, with or without you.

*

Both of the younger poets in this group turn in virtuoso performances. Melanie Siebert’s debut collection, Deepwater Vee, (the title indicating “a tongue of dark, glassy water that points downstream” and makes for tricky navigation) travels a Canadian river wilderness that is both remote and threatened. Having worked as a guide from Alaska to Baffin Island, she knows her territory well. And loves it. Acutely attuned to her terrain, Siebert’s evocations are attentive and unique: “river, slow, shambling, smelling like grain,” or “the under-river… volts of its silver pins-and-needles porewater. / Its tai chi empty hand, single / whip, slow now, outwash / undersound.” In “Unnamed Creek,” “You’re… brittle… and old as lichen. / The smell of decay rides its ship over the edge of the world. / Terns pour their dye into the wind and show you its limber lines.” Partly rescue mission, many poems alert us to environmental disaster, inch by painful inch: “North Sask wobbles into the underbrush voice box. / Acid rain trucks in from the tar sands.” The poem ends with the disturbing mantra “You can’t drink this water. / You can’t drink this water.”

Seibert’s language suits its subjects, either soft as a lullaby or muscular as wild weather and tough territory: “clouds musk-ox skulled and bossing in,” waking “ancient in the night… under the thunder-flask, glaciers calving bergs.” Sometimes the language gets over-technical. In “Bridge to Shell’s Albian Mine, Downstream, River Right,” the words are compelling, materially fascinating but, for one outside the complicated process described, confusing.

This same poem begins “We were taking samples of water” and “wanted to know what was coming down the feeders.” Who is “we?” The subject of the many exhilarating and dangerous adventures in this book is often unclear. In watery drifts, Seibert braids together Alexander Mackenzie’s dreams, a broken-down street busker, and a wandering grandmother until, to use the words of the title poem, “you play out converging currents, sloppy haystacks curling / over the gunwales, less and less freeboard, / bailing on the fly… weighted here” and the riveting ride stalls because structurally and narratively there is too much going on. As Siebert paddles her rivers, we do not always know which voyage we’re taking or whose: Mackenzie’s, hers or First Nations Keepers of the Water. While this may not diminish the overall impact of the book, it makes for slightly agitated reading due to the wealth of historical and technical particulars that constitute Vee.

The grandmother poems are particularly affecting. This iconic figure, straddling time and place, is Siebert’s Mother Courage. In the following prose poem, she is “Asylumed to back roads,” she “sleeps days in a rusted-out car parked in the deepest grass” and later “rolls down the window, and waves him over.” Together “they listen to the little piano of the rain… He curls up on the bench seat… head on her lap. Migrating birds rest on the hood of their broken-down, their not-moving. And she combs the voices out like the burrs in his hair. Peace now, weather is weeping. Ride this continent out onto the dark seas.” Mackenzie himself emerges heroic. Worn and battered from this harsh northern world, he “has tromped the grease trail with two pistols under his belt, / hacked a road for commerce through the hot flank of the fleeing deer… frozen now and lapping in his hip, ailing and suddenly old.”

The buried impulse of this bracing and deeply felt book is genuine myth-making. Many poems approach that edge but do not go further. The elemental images of “Double-Barrel Lake” jostle for power: bedding down in the northern lights, “in the fat spoor / of a solar wind,” where you have been emptied out to “Heart, / eye’s blackness / on which light moves.” Here is where the super-charged reality of myth aches to begin but is left unrealized.

*

Short and to the point, Sandy Pool’s Exploding into Night hits you in quick scatter shots. Each packed prose poem hunches threateningly on the prim white page, gathering forces for its own blast of violence in Toronto’s Parkdale district. Pool sets the scene with telling detail: “Here is her street at dusk… open-mouthed, desolate. Tulips long dead… panic of needles, small wasps crouching in sand.” In this urban wasteland, even the lake is dying. Everything reeks from “the absence of love.” Warm and wet, swaying with streetcar tracks through an underwater city, sexual assault occurs like an escape act that “shucks the self nightly” leaving “sperm… in my hair” and a “jellyfish heart bloating, raw and iridescent.” Lovesick pigeons mewl and grapes rot on the windowsill.

Artistically, Pool is chameleon. Dramatic moments tighten into urban legend as scenes flick by with an almost film-noir cunning. One feels the easy influence of cinema and the visual arts in this work.

These poems follow an increasingly harrowing narrative, shifting nervously between violences, whether intimately domestic or anonymously urban. Suddenly the sad sexuality changes. There is shock in a newspaper headline. “She” wonders, are there “bits of her stuck under his dirty fingernails?” She gets pregnant. He continues philandering. They retreat to separate apartments while “conspiracies collect like sediment,” she recalling how he threatened to kill her over something to do with blood dripping from the roast, either too rare or not rare enough. Eventually, the marriage doesn’t end; it dissolves “as soap in water.” They drive north over blasted roads past raccoon corpses but cannot stop needing each other, like fish drawn to lures or a knife to the chopping block.

Almost imperceptibly, atrocity is committed. The charged tone does not alter, nor does language, but the narrative perspective changes: “You have made me into air… my limbs ghost the hallways of our apartment.” She is alive and not alive: “They found me on Remembrance Day in shopping carts and duffel bags. Hands missing.” There ensues a sort of necrophiliac metamorphosis: “We spent three days together. My body shipwrecked, entombed in white porcelain… I had become beautiful… grown scales and a black, liquid eye.” This disturbingly familiar event, in Pool’s theatrical imagery, surrealistically rearranges an urban landscape. It also asks: which “she” is carved up in dumpsters, pulled from the water, “glittering and stupid,” absent on Christmas cards now, remembering his body, “a flash of minnows exploding into night?” Pool’s ambiguity feels deliberate. While still projecting the pain of individual violation, by a deft slip-sliding of narrative perspective “she” becomes collective, becomes every “she” ever murdered.

*

Always controversial, poetry prizes have a pedigree going back to the Greek laurel wreath. In their unbridled proliferation, have prizes lost gravitas? Have we become numbed by them? Have we tuned out? Given the dizzying range of tastes and trends, do prizes unite or divide a literary community? The New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik refers to Nobel winners, for instance, as those with a neatly delineated social view, writers of “the world-and-its woes” as opposed to writers of “the-sentence-and-its-structure.” No doubt, similar splits exist in poetry prizes: between, say, post-confessional poets and language poets, with the categories changing all the time. Are we pleased when our fellow writers win, or resentful? Moneyed prizes can make a substantial difference to any artist’s output and wellbeing, but how generous do we feel when the cash goes to someone we regard as undeserving? One might argue that prizes raise literary awareness, but so do many other mechanisms, including, these days, literature online. Including solid criticism. Canada Reads actually gives the task of choosing winners to discerning readers, public personalities though they may be.

One can be sure that where there is literary life there will be prizes. Where there are prizes, there will be dialogue and debate. The real value of the laurel leaf may be symbolic, reliably indicating the health of the literary culture it stimulates.

Boxing the Compass by Richard Greene was the recipient of the 2010 Governor General’s Award for Poetry.

Patricia Keeney is the author of nine poetry collections and one novel. She is a critic and editor, and an English and Creative Writing professor at York University in Toronto.