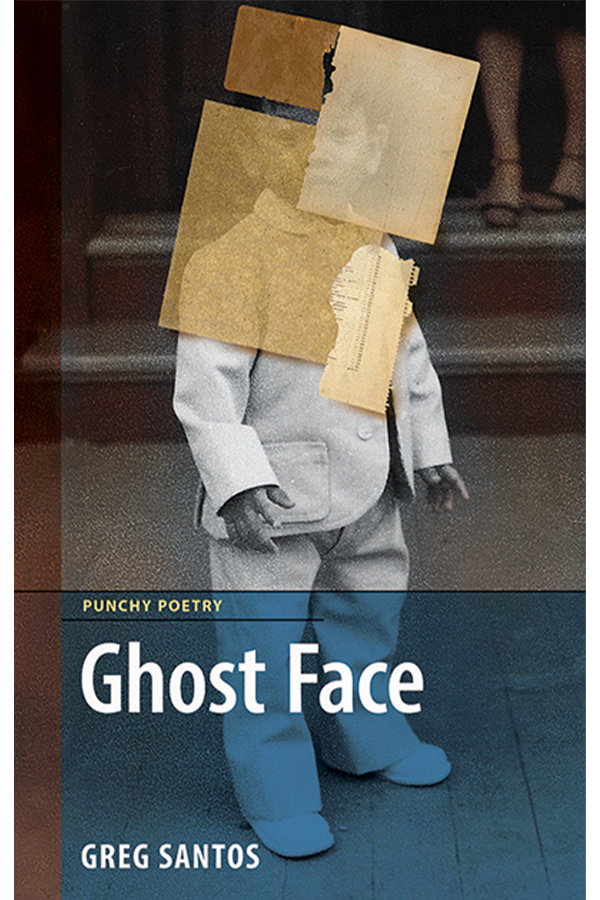

Greg Santos’s third volume of poetry, Ghost Face, marks a unique entry in Canadian literature. He is one of few contemporary writers in the country whose breviloquent words paint a big picture.

A Cambodian adoptee, of Cambodian, Portuguese, and Spanish heritage, born in Montreal, Santos is a poet, educator, and editor-in-chief of the Quebec Writers’ Federation carte blanche magazine. His is a city where heritage takes a prideful refuge. And in a country where survival means everything to literature, his take is decidedly different: “Now, who are you? // No. Pay attention. // Let me answer for you: You are nobody. You don’t really exist. … I’m just trying to get to the bottom of things.” (Let’s Start at the Beginning)

Santos handles language as a dramatic vehicle, to say that which cannot be expressed unartfully. In “Siem Riep, Cambodia” he depicts his own gestation, describing his mother fleeing Angkor as “another one of their children flees, / taking nothing but me, / gently growing inside her.” Then he follows up on the next page with “Cambodian,” concluding, “It’s like you are actually Cambodian or something.”

What’s said not only between the lines but between the pages of Greg Santos’ poems expresses his alterity, his liminality, and ultimately, his presence. There is an express absence of comfort and, as a result, his words remain sparing.

In his poem “I’m Dog. Who Are You?” he speaks of fatherhood with restraint, in response to a New York Times article on the fallout of the Khmer Rouge and the Cambodian genocide: “In Cambodia … Words were used as knives. / Children would turn on their parents. / The wrong sentence was a life sentence.” His poems are always an inclusive sort of self-portraiture, the poet present but illusive, yet painfully self-aware. The writer intimating his familiarity with parenthood without fully knowing himself. He ends this poem, among others, with bathos: “I’m dog. / Embrace my dogness. / Are you dog, too?”

His identity as an adopted child came to him as he grew older, he says, stating in previous lines that for a long time, he didn’t even consider himself Asian, not knowing much of that side of himself. What Greg Santos provides on the page is this glimpse into the stuntedness of his identity as poet, child, man, father, Cambodian, and Canadian. He is vulnerable, unsure, but resolute, refusing to be broken after building up this idea, this image of himself his entire life. This grief, this unknowingness, defines the ghost in Ghost Face. That he was able to accomplish this in his third full-length book of poems demonstrates the brilliance with which his pen moves across the page.

Ghost Face exhibits a variety of poetic forms, but what takes time to truly appreciate is his technique of spacing words. In the short poem “Khmer for Baby,” for example, each line appears sparse on the page, producing the effect of visual lacunae as the writer brings words to memory. Did he have a name, he asks the page, or was he known simply by the Cambodian word for baby, tearok? In this way, he draws the reader into his experience, grasping for answers from intergenerational trauma and his heritage tongue, and imparting his pain as proof of his growth, his questions as waypoints to a deeper sense of self.

To say Santos’s poems are haunting would be an understatement. The poet within Greg Santos has only just arrived.

Bios

Jay Miller

Jay Miller is a poet, translator, and technical writer who lives in Montreal. He is currently learning to code, with a keen interest in Julia, data engineering and scientific programming. He can be found on Github and Twitter @sootynemm and on Mastodon @sootynemm@troet.cafe. His work can be found listed on sootynemm.com. [updates in 2023]