E.D. Blodgett. Apostrophes: woman at a piano. Ottawa, Ontario: Buschek Books, 1996.

E.D. Blodgett. Apostrophes VII: Sleep,You, a Tree. Edmonton, Alberta: University of Alberta Press, 2011.

E.D. Blodgett. Praha. Edmonton, Alberta: Athabaska University Press, 2011.

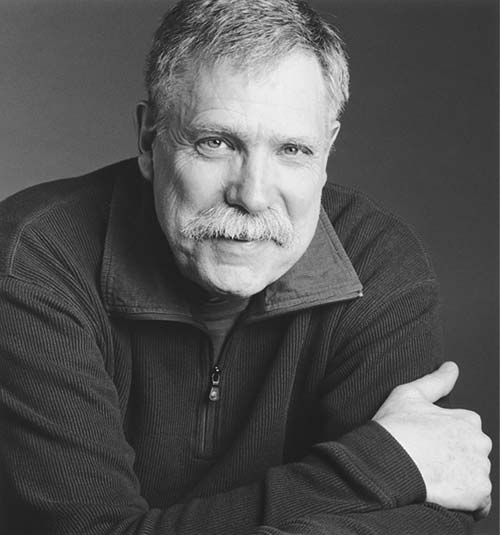

~ reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

These two series of poems belong to that culture within Canadian poetry that eschews clarity for the resonance of transitory states of intuition at the edge of consciousness. In the work of many poets, this approach is rooted in the emotional and cognitive fields cast up by words. In his earlier work, Blodgett is more interested in the resonances cast by the body and in the interplay between words and consciousness, which result in multiple possibilities—quantum states of poetry. In Apostrophes: woman at a piano, for example, that flow can progress through easy stacks of phrases, connected with commas and moving forward in causality, as when “eternities / in dream begin, a flower, rains of silence in the air” (“Full”), but that can also abruptly change and flow backwards in time. The poem quoted above, for instance, twists its syntax and stops it in its tracks with “seasons [that] lie within your eyes, / birds coming back to settle there,” whereas elsewhere the poem pools in time without moving at all: “The sun’s fate is in your eyes, the fire unfolding the / inevitable rose, eternity exhaled without a sound.” To pull off this shunting through his hypnotizing patterns of repetitions, Blodgett makes ample use of commas as markers for a pause that is continually changeable, and often readable only by going back and inserting an appropriate tone once a misreading becomes apparent. Such thinly supported demands upon readers make this a sentimental method. In the newest instalment of this sequence, Apostrophes VII, Blodgett’s cognitive sequences are much more tightly controlled. Instead of shifting in causality, they shift through meaning. In “Smile,” for instance, “falling on your face / as rain that falls that is not felt as rain” is modified with “only its falling known” — simultaneously a thought deepening the perception of rain and one that stands apart from it. This self-referential distance progresses even further in “Collapsing,” into discourse that inserts the world into a position formerly held by human consciousness: the direction of a sentence’s thrust. “What else,” Blodgett asks, “is there to carry walking near / the clouds remaining by our sides?” (“Collapsing”). The question is a trick, just as Williams’ red wheelbarrow was: it proposes a question that, once read, brooks no answer but itself. It is all syntax and no intent at all. “This,” Blodgett notes, “is our us, the rest / the disappearing simulacra of a world barely known” (“Collapsing”) and which, it’s important (and sad) to remember, he had a closer handle on when he was younger. These depersonalizing effects are even more prevalent in Blodgett’s long sequence about Prague, Praha, which is about the spirit of a city rather than its physical or social form. In Praha, all commas, capitalization and other signposts are replaced with pauses. The shifts orchestrated by commas in the Apostrophes sequences are now abrupt shifts of dual meaning through mechanical line breaks, based on hypnotic and sometimes overly rhythmic structures. Whereas across the span of Apostrophes Blodgett created complex, two-handed piano music, throughout Praha the cyclical drone of an organ asks readers to stop and go back and listen again: “as if one were to gaze // into a mirror to / discover there was no / possible // as shadows cast by stars / across the night” (“Boulevards”). The syntax here suggests meaning but the words provide none. Sentence by sentence, the poems in the Apostrophes sequences dazzle with their dexterity and dualities, yet fail ultimately to build a body to hold the poems in the air. The fault largely lies with loose, prosy stanzas. In contrast, it’s exciting to see tight line breaks and rhythms in Praha as Blodgett replaces his rather random stanzas with tight couplets and triplets, often rhyming and built upon clear metrical structures, which repeat over and over. The repetition becomes numbing, at least for this reader. Such hypnotism is Blodgett’s point about Prague, but in the body it doesn’t ring true. Despite all the sonorous music, the body does not get up and dance in the dream city of which Blodgett does, at times, give tantalizing and haunting glimpses.

Harold Rhenisch’s eleventh book of poems is The Spoken World (Hagios Press). His long poem in Chinook and English, North West (Ronsdale), is appearing in 2013. He lives in Vernon, BC.

Explore the culture of Canadian poetry with Arc!