In The Wig-Maker, Janet Gallant’s tragic and transformative memoir-as-serial-poem written in collaboration with award-winning poet and editor Sharon Thesen, the art of wig-making anchors the text as both vocation and metaphor for healing and self-creation. A kind of time-travelling polyphonic bildungsroman, The Wig-Maker narrates a story of graphic violence, sexual abuse, racism, and parental abandonment that is shocking both for its plain-spoken depictions and for its desire to understand the human beings who commit these brutal acts: “My whole life I’ve had this yearning / but loss just comes” (“questions unanswered”). Gallant sings the “moan” of her life and the life of her family through the lyric lineation of Thesen’s verse, like a libretto for an opera soon to be composed.

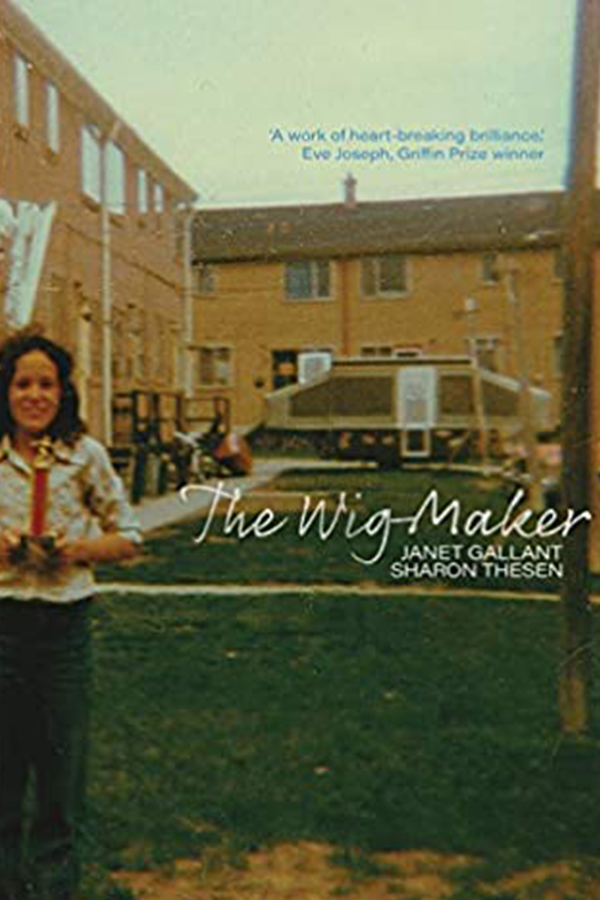

Gallant wasn’t always a wig-maker. She became one because she lost her hair, when she was diagnosed with alopecia at forty-five. For Gallant, the making of wigs is also a making of self: “I think I had to go bald to see myself, to lose my hair to start / looking / at myself” (“alopecia”). Thesen’s poetic hand is evident in the line break. The enjambment separates “looking” from the syntactic flow, the double Os like a set of glasses inspecting the reader as much as the speaker. Gallant’s intimate first-person voice is expressed in Thesen’s loose, triadic stepped-line stanzas. This intimacy is interspersed with photographs of family, of wig-making, and of Gallant as a child. In combination with the elements of memoir, the photographs turn The Wig-Maker into a kind of family album that curates a comprehensive history, rather than picturing only typically “good” moments. While Gallant’s family would like her to forget and “leave the past in the past” (“valerie johnson”), she struggles to document, remember, and understand: “I need to get to the bottom of this…I JUST WANT A STORY” (“october 2019”).

An “energy of fear” (“the neighbour”) runs through Gallant’s voice but prose fragments interject to offer detail and perspective that would not be possible with only the first-person point-of-view: “Eventually there comes a moment [while making a wig] when she feels there is someone in the room with her – a life, a fate, a personality” (“penny”). Bits of context—history, DNA results, realities of the international hair market—bring the outside world into the text. The narrative moves forward and backward in time. Thesen’s deft structure slowly accrues fragments as the larger text coheres for the reader. As the text braids together different elements, a wig is “ventilated” (“penny”) with thousands of individual hairs, tightly knotted to an almost invisible lace.

Maybe this voice is Thesen in her role as “conduit of this tale” (“afterword”) or maybe the shift to a third-person narrator is meant to trouble the unity of the text as a whole, to embody overlapping identities simultaneously to create a “dynamic relationship between maker and made” (“afterword”). Gallant encounters “a life, a fate, a personality” in each wig she brings to life. She listens for her family members who didn’t survive abuse, for the “moan,” the wordless song of pain that is “the vibrations of the soul” (“the neighbour”). The Wig-Maker is a song from a “house of moans” (“tom”) where spectral voices come forth finally to be heard.