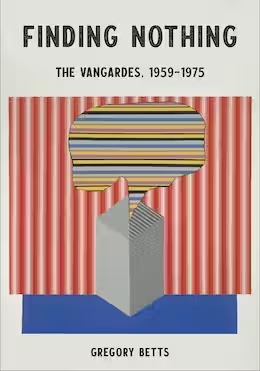

Gregory Betts’ Finding Nothing is a characteristically astute study of the Vancouver avant-garde that nevertheless surprises. Also interesting is the fact that its format—which includes over one hundred illustrations, many of which feature VanGarde artifacts from Betts’ private collection—makes it almost as much a book of textual and visual art as a work of scholarship.

Betts argues that the abundance of new ideas and models, while flowing into the ostensible artistic void of mid-century Vancouver, in fact mirrored and was directly related to the colonial displacement of Indigenous peoples, with the local something that had been present obscured for new arrivals who “could not see what they did not know to look for.” The writing of the 1950s generation, Betts continues in his introduction, moved itself “out of the colonial mentality just enough to begin to stop the erasing”; instead, they located themselves by taking “themselves and their city as their subjects and found a very different story than what they had arrived believing.” Reversing the “overlapping erasures, the enforced nothings” that structured perceptions of Vancouver, the ensuing “VanGardes” developed new artistic approaches by applying international movements to a local scene that was being simultaneously uncovered and built anew. Individual chapters fill out this conceit with arguments about (among other things) the primarily social and professional influence of Tish as contrasted with the “radical openness and investment in eclectic disharmony” that defined bill bissett’s Blewointment; the underappreciated robustness of Canadian concrete poetry that is revealed by redefining the latter as being not a school but “between a method and a worldview”; and the distinctness of the birthing story from the teleologically oriented Künstlerroman.

Given perennial denials that a contemporary avant-garde is even possible, there’s a familiar advocacy here. Betts’ distinction between avant and non-avant (and post-avant) art hinges on the avant’s possession of a concretely revolutionary politics—even if the latter might also be primarily quotidian or aesthetic… provided the artist has the correct politics (being, for recent avants, a commitment to decolonization). For me, these formulations don’t quite address the fact that art with undeniably radical aesthetics has been made by people with extremely conservative politics. (Wyndham Lewis comes to mind, although, to be fair, Betts does “set aside the question of modernism”). Conversely, there are contemporary poets with the furthest-left politics imaginable who write what would in any other context be called free-verse poetry—poetry many would describe as aesthetically conservative. Betts’ system creates conditions for re-evaluating Lewis as not-avant, or a leftist free-verser as holistically radical. In doing so, however, it’s a reclassification of who is avant according to criteria other than what might be remarked in the aesthetics of the works themselves (and one that, unfortunately, fits into the culture-war binary that circumscribes so much discourse).

But these are minor quibbles given that this astonishingly comprehensive volume more than justifies its premise. Betts is also as extraordinary a scholar as he is an idiosyncratic voice. He refreshingly admits into the fold some work from those recognized as lyric poets; there’s also evidently beef with Frank Davey. The book’s conclusion follows the succession of avant-generations jarringly into the present; its penultimate chapteron the post-avant provokes as much as it validates Betts’ periodization. Given constraints on space, I’ll end with some critical nothingness of my own. In following Betts’ formulation, doing so should also leave his bleak conception of a post-avant world to be engaged—generatively, I hope—by other critical voices.

Bios

Carl Watts

Carl Watts holds a PhD in English from Queen’s University and teaches at Huazhong University of Science and Technology. He has published two poetry chapbooks, Reissue (Frog Hollow, 2016) and Originals (Anstruther, 2020), as well as a short monograph, Oblique Identity (Frog Hollow, 2019). A collection of essays about contemporary poetry culture in Canada, I Just Wrote This Five Minutes Ago, was just published by Gordon Hill Press. [updated October 2022]