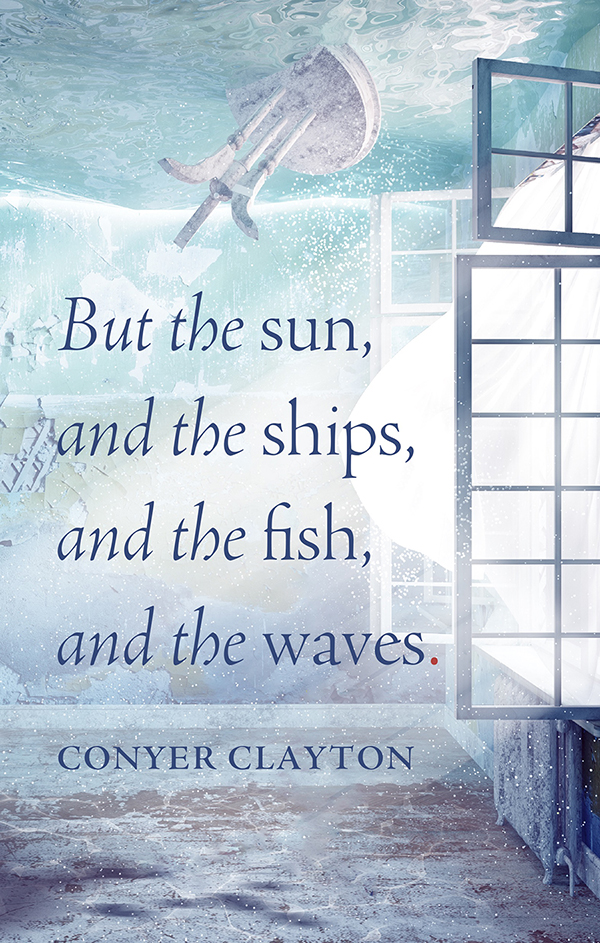

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD), which according to poet Conyer Clayton is at the “core” of But the sun, and the ships, and the fish, and the waves, is a disorder that requires a lifelong commitment to healing. But while the back cover blurbs designate Clayton’s sophomore poetry collection a “testament to survival,” a change in tense is necessary to correct this misnomer. For the book is not a testament to survival, but rather, it is a powerful and exquisitely crafted testament to surviving.

Surviving trauma can be likened to addiction: one’s self is always in recovery. Given the ongoing nature of survival, Clayton’s book has an air of unfinished business—as if the speaker has more to learn: “I need to understand,” the speaker pleads in the final poem “Brand.” This desire to know and understand the past also highlights a shift in the speaker’s perception—an important step in any therapeutic process, especially in cognitive and dialectical behavioural therapies.

But looking back and wading through the past can be merciless. It can be disorienting, unsettling—dangerous even. To create a sense of disorientation and to capture the inherent risk of processing trauma, Clayton performs a deftly executed poetic legerdemain to confuse dreams with reality. The poems follow no logical chronology, nor do they adhere to any rules of realism. Scenes ebb and flow. Tender moments shift into violent fantasies and graphic descriptions of sexual assault. Bodies cause pile-ups. The woods stare back and shame has a tail. Tire tracks reveal futures. And funhouse-like mirrors work to further distort the speaker’s subconscious reflections.

Revisiting these reflections, whether warped or not, is a vital exercise, despite the accompanying body-mind discomfort, for mindfulness practices result in positive changes in behaviour and core beliefs. “The habits I build today will last for the rest of my life,” says Clayton’s speaker; however, creating new neural pathways does not happen overnight (“Growth”). In time, she explains, “[w]e learn to process what we take in, generate energy from something then nothing then finally [we are] self-sufficient” (“Lone Mouse in Empty Space”).

To interact with and interpret memory, grief, and trauma as safely as possible, poetry is the speaker’s chosen medium. “[P]ut the words inside [the poem], but you cannot go inside yourself. You must stay out here,” advises none other than renowned poet Dionne Brand in “Brand”. “We peer”—into the poem, the house, the past—the speaker says. Surviving is not a solitary act; and so, in this brief yet poignant interaction between Brand and the speaker, Clayton draws attention to the essentialness of support.

Clayton’s exemplary collection of surreal prose poems teaches us that surviving CPTSD is a lifelong process. A process whereby we learn to move “beyond the break.” Beyond “the sun, and the ships, and the fish, and the waves”—all those extraneous details threatening to anchor us in the abyss (“The Break”). Because those who stop treading water and “forget how to fight for life, […] are the ones who fall screaming” (“Love Interest”).

Bios

Elena Bentley

Elena Bentley (she/her) is a disabled, bi, and Métis/settler poet, editor, book reviewer, and children’s book author from Treaty 6 territory. She is a Citizen of Métis Nation-Saskatchewan, and she holds an MA in English from the University of Toronto. Her poetry has been published in various magazines and journals, including Arc Poetry, The Malahat Review, PRISM international, Room, and Grain. [updated November 2022]