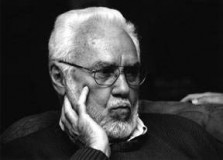

~ remembered by Shane Rhodes, Arc poetry editor

To speak of Robert Kroetsch, I need to first talk about some places.

Kroetsch was born and raised in Heisler, Alberta—about an hour and a half from where I grew up in Alix—a place that requires repeated taps on the Google maps zoom-out button before you begin to understand where exactly it is (close to Donalda, Forestburg, Strome). This is a place still on the edge of nowhere, a place that, compared to our cultured cities, seems destined to oblivion as soon as you drive through it on your way to Edmonton. But this place, and many others like it all over Alberta and the prairies, a barely-even-there on-the-edge-of-ghost town, was Kroetsch’s literary home. Rather than being embarrassed by western/prairie culture and its historic desolation—made up as it was of generations of new Canadians from all over the world clearing land, planting seed, pounding fence posts and shaking their fists at clouds—he showed us that the culture we had was both rich in imagination and could form the flimsy bedrock of crazy fictions and poems.

Growing up as a writer on the prairies, more than most anyone, Kroetsch made it okay to write from places like this rather than in the lyrics of some imagined Europe, Eastern Canada or America. This writing from place (what, I think, was once dismissed as regionalism but is something far greater) is the start of the radical honesty that permeates Kroetsch’s writing on everything from geography to love, sex, being young and growing old. It is an honesty, slow burning as Cigar Lake uranium, that will power his books for decades—an honesty that can only come from telling stories.

Kroetsch was a poet. Even when he was trying to write novels and books of non-fiction, he was a poet. But, with a formidable presence in both genres, Kroetsch also brought to Canadian poetry a narrative fervour—you only have to read a few pages of the Seed Catalogue or The Sad Phoenician to realize they are murder mysteries and romances just as much as they are books of poetry. Starting almost any of Kroetsch’s books is starting on a form still finding itself and a story unlike many heard before. Reading those books now—many of my favourites were published over twenty years ago—the experiments feel just as new as they must have felt when originally published.

Many others will write about Kroetsch’s long-lasting influence on Canadian poetry, literature and criticism, and about his generosity as a teacher and mentor. Rather than repeating accolades, I end only by saying that Kroetsch will be missed and should be missed. And, really, is there any other Canadian poet who has written so well and so often about absence and missing? With that lack, we can take one of his books from the bookshelf—maybe the Completed Field Notes—and try to find him again.

I have sought my mother

on the shores of a dozen islands.

I have sought my mother

inside the covers

of ten thousand books.

I have sought my mother

in the bars of a hundred cities.

I have sought my mother

on the head of a pin.

I have sought my mother

in the arms of younger women.

I have sought my mother

in the spaces between

the clouds.

I have sought my mother

under the typewriter keys.

#2, The Poet’s Mother, from Completed Field Notes: The Long Poems of Robert Kroetsch, University of Alberta Press, 2000, used with permission from Westwood Creative Artists. Photo credit D. Schaub; used with permission. Copyrighted materials; may not be reproduced without permission.