2.

“… We’re all // so full of love and blood.”

—Joelle Barron, “Galiano 2”

30 Under 30, a new anthology of poets born after 1986, published by In/Words Magazine and edited by a.m. kozak, lives partially in this tradition. It is a work of praise for sure, but it doesn’t share much of its predecessors’ interest in maps or strata. Unlike these paragraphs’ second and third texts, Breathing Fire 1 and 2, which were edited by University of Victoria professors Lorna Crozier and Patrick Lane, it is a product of the same generation it presents. kozak could have picked his own work for the book, if he had wanted to. It was published by a university outfit. It is hard to find in stores. Its title is such a listicle cliché that disappears down the deep well of Google searches.

3.

“Could she be one of ours?”

—Patrick O’Reilly, “Strazza’s Virgin at the Presentation Convent, St. John’s”

The first Breathing Fire anthology was released by Harbour Publishing in 1995. It contained the work of 31 poets born in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Some of those poets are now at the middle of our national poetry (Karen Solie, Evelyn Lau, Karen Connelly, Sue Goyette, Michael Crummey) and some have less-recognizable names. It was dedicated to Purdy and contained a delightfully phoned-in introduction from the elder statesman. Purdy’s contribution was seven sentences long. One of them read, simply: “I think these are excellent poems, much better than the work of my own earlier generation.”

4.

“Dear body, // I want to take / the beating for you.”

—joseph ianni, “heart beating (part ii)”

Crozier and Lane’s own artist statement was grandiose and traditions-fixing. It praised and mapped. It employed the kind of liberalism that today’s readers, raised on intersectionality, are excused for cringing through. To wit: “We avoided the temptation to use criteria such as gender, race or location, which might have helped us with our choices at the expense of merit.”

5.

“I unstitch myself for you but I will not wear these clothes again and you cannot have me”

—Emily Chou, “the crane wife (a haibun)”

Twenty-plus years later, we forget that it mattered whether poets got into Breathing Fire. Middle-aged ones with audiences and teaching jobs will still complain about their omission today. The book became a kind of foundational document, or cheat sheet, for understanding the breadth of new Canadian poetry being written. The great majority of its 31 poets were unpublished in book form. The great majority published first collections within a few years of its release. Breathing Fire was a catalogue for poetry publishers. It was a debutante’s ball.

6.

“wiggle your shins almost like you were a ladybird”

—Kate Hargreaves, “(practice)”

The experiment was replicated in 2004, with a new crop of young writers, for Breathing Fire 2. This included Shane Book, Joe Denham, Autumn Getty, Alison Pick, Matt Rader, and Sue Sinclair. Crozier & Lane’s eye for consequential poets was stronger, I at least recognize every name in the contributors list. As editors, Crozier & Lane’s job had gotten easier because, in the nine years between editions, what it meant to be a twenty-something poet had changed. As they confirmed in the introduction, “Though the majority of the contributors to the first edition were relatively unknown at the time of its publication, the writers in this edition have already received astounding recognition.” By this, they meant: they’ve published books, their names got in the paper. They’ve won contests and readerships. They took less effort to find.

7.

“I wonder how this remembering will work,”

—Selina Boan, “Rivers in Waterhen Lake (command f for find)”

Breathing Fire 2 was released the same season I started taking poems seriously. I recognized, in it, a grave and baffling seriousness. An institutional push behind the love of new writing. Scary, polished, and self-serious to the point of parody.

8.

“I can imagine a better world. / I’m a good fit for this position.”

—Jay Ritchie, “Multi-level Marketing”

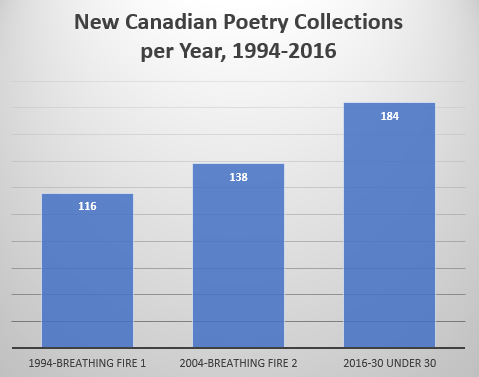

Is it too simple to speak of numbers? Here are some numbers. In 1994, the year that Breathing Fire 1 was being prepped for publication, there were 116 new collections of poetry published in Canadai. In 2004, when Breathing Fire 2 came out, there were 138ii. And last year, 2016, saw 184 new poetry collections published in Canadaiii. Here is that visually:

9.

“The bug that bug had for lunch, if that.”

—Kayla Czaga, “SELFIE”

This represents a 19% increase (22 books) in the years between Breathing Fires, and a further 33% increase (46 books) from Breathing Fire 2 to 30 Under 30. That’s significant. And I bring it up to suggest a central change in the environment that responds to these anthologies. Breathing Fire 1 was about grooming nearly-ready poets for the stage of a full-length collection. It was about the possibility of publishing.

10.

“the sort of adventure for which I / feel the utmost adoration but / no need.”

—Bardia Sinaee, “Ornamental Kale”

Breathing Fire 2 and especially 30 Under 30 are as much reactions to the problem of publishing as its possibility. The new book includes many poets without full collections released or planned, but there are a dozen names in its contributor lists likely to be recognized by anyone plugged in enough to contemporary Canadian poetry to be reading these paragraphs. It contains winners of national awards, and writers whose presence in our major journals would be more of a thrill for the journal than the poet.

11.

“Rubbing feeling back into my fingers.”

—Chris Johnson, “Bashō and I popped out for a pint; B said beer goes down like raindrops into the bucket”

As a public introduction then, 30 Under 30 is redundant. Happily, a public introduction does not appear to be its goal.

12.

“We left out / the backdoor, a blowtorch taped to a knob / of a hockey stick.”

—Curtis LeBlanc, “Imperatives”

There is something else happening in 30 Under 30. As an anthology supported by poets who can and do find publication all over the country and beyond, it’s not beholden to the same breathless ambition of the Breathing Fires. Here, the published poems aren’t always the authors’ best, but they are often their funniest. The humour is poised, dry, and in-jokey. It is cliché to speak of poetry turning inward, and I don’t offer this as a straight criticism, but I do feel that the audience for 30 Under 30 is its contributors, both in the literal sense and the broader demographic one. It’s an introduction to millennial poets written for millennial poets. Nobody is showing themselves off for the grown-ups. The point, here, is to show to your peers.

13.

“Sometimes I do it so others can see it.”

—Julie Mannell, “Poems Against Pretty Bodies”

The point is to show to your peers is a stubborn sentence, and a potentially disobliging one, if you’re not among the peers. I don’t know what to say except it doesn’t make me like the book any less.

14.

“… How wholly / unremarkable to be in each others’ lives.”

—Jessica Bebenek, “The Future of Condo Living”

It’s useful to consider 30 Under 30 as a yearbook. It comes complete with a yearbook’s stylistic tics, like didactic prose (kozak’s opening essay reads like every Facebook defense of millennials, mashed together) and gags in the biographies. As an object, the book has an ISBN and that’s about it. Its Staples-quality pages stick together. Once the cover is bent, it stays bent. I have never seen a copy in a bookstore. Most people seem to have gotten theirs at parties.

15.

“… when I go away / people will look and think / they belong somewhere”

—Adam Zachary, “is it raining?”

Mine was hand delivered, quite generously, in a rainstorm by the contributor who lives closest to my apartment. The book is a commodity, sure, but it is only, in the barest way, public-facing. It is only begrudgingly capitalistic. Poets are ordered by age and get a single poem each. There are no photographs. The sense of the genre as a series of perfect-bound CVs, central to Breathing Fire’s careerist pomp, is absent.

16.

“in what godforsaken universe would the angels be humanoid…”

—Ian Martin, “THE FUNNY THING ABOUT PATTERNS IS THAT ALL OF THEM CAN BE FOUND”

I must come clean about something that worries me. Sometimes when I say that 30 Under 30 and Breathing Fire are different, I am pointing to this difference as a way of measuring the cultural history between them. And sometimes I’m not, I’m pointing to editorial differences that are ahistorical at this time-span, differences between Crozier/Lane and kozak, differences not explicitly representative of their decades. Sometimes, my figurative overreach is so bad it breaks the nearest argument, as when the books are different in contraindicative ways. The Breathing Fires are more superficially professional, as objects, than 30 Under 30. They are beautiful and sharp. They had optimistic print runs. Is such professionalism on the decline in Canadian letters? No, I don’t think so. Does this make the kozak effort less successful, with its sticky pages and small circulation? No. Or at least: I don’t care. As you read the next few paragraphs, please understand that I don’t care.

17.

“to read like a regular person…”

—Jessie Jones, “Better Manifesto”

The unspoken currency of the more bourgeois anthologies, especially the Breathing Fires but Purdy’s Storm Warnings too, is the tantalizing prospect of the wunderkind. We’re invited to judge these anthologies by how many special assets were found before their blossoming. The Breathing Fires cared about capturing wunderkinds.

18.

“yer but / the decompositions of yr core.”

—dalton derkson, “the reasons we drop ourselves on our heads”

Whenever we talk about youth and art we hint that another way of doing things is coming available. That’s the promise of the wunderkinds. Even if the work itself doesn’t shine with newness (the straight-ahead CanLit-ness of the Breathing Fires inspired much backroom complaining and at least one parody anthology, Jay MillAr and Jon-Paul Fiorentino’s Pissing Ice: An Anthology of “New” Canadian Poets) it is easy for an impresario to suggest in the presentation of an unheard talent that another world is there to be discovered.

19.

“my hands are infants that / need to grow up to hold me”

—Klara du Plessis, “Om rond te tas / une tasse”

But this gambit—I’ve called it bourgeois once already—is a growing industry inside CanLit. Breathing Fire was the vision of two university professors. Its currency came from the mentors and authorities who invested in the primacy of their taste. There is something tactical about this. To take a new voice and publish it in something like Breathing Fire is to place it in a tradition before its time, to demand an acquiescence to the structures of CanLit before the voice can force the structures to acquiesce to it. Being in a Breathing Fire was catnip to two decades worth of granting juries. It made a generation of Adjunct Professorships.

20.

“Like, if all my father figures are trying / to fuck me, do I still have daddy issues?”

—Cassidy McFadzean, “Ten of Swords”

If the wunderkind gambit is bourgeois, it’s also optimistic. It’s embedded in the classification we give our would-be wunderkinds: our “emerging” poets. Emerging assumes that its counterpart, established, is also meaningful and defined. But of course, established poets are also always emerging; they are still underdog artists, known to the public only occasionally, when and if their work butts up against the zeitgeist. Right now, there aren’t any established poets in Canada. In Canada, the only kinds of poets are emerging and deceased.

21.

“I’m still shaking monkeys off my impersonations.”

—Adele Barclay, “When Does the Hunger Begin?”

The ethic of Breathing Fire is still alive, even if the anthologies seem to be over. The Bronwen Wallace Award is sponsored by a bank and administered by the Writers’ Trust. It started in 1994, the year before Breathing Fire 1. It’s open to writers under 35 who haven’t published a trade collection. As you can imagine, it’s common now to see finalists that fit under this limit by a decade, who go on to have two books by the time they age out of the contest. Case in point, one poet well-established enough to judge the most recent Bronwen Wallace was 30 Under 30 contributor Adèle Barclay. A second, Moez Surani, was still in his 30s. The founders of the Bronwen Wallace chose 35 as the cut-off because their namesake published her first book at that age. The demographics of the emerging poet have shifted since Wallace wrote Marrying into the Family in 1980, and they’ve shifted again since 1994, following the demand of those 184 publishing slots a year. As recently as 2005, we had one MFA program in this country. Today, we have five. We are making more emerging poets, and establishing them earlier.

22.

“Then all of us together gave up on you.”

—JC Bouchard, “Kaleidoscope”

Any shift in values from Crozier & Lane to kozak needs to be expressed within the context of those 46 new poetry collections a year, and the flow of professionalized young poets there to fill them. While publication’s supply has increased since Breathing Fire, the best poets’ demand for it might be weakening. There are trade publishers listed in the poet biographies of 30 Under 30, but there are more micropresses, collectives, and chapbook shops. Even the most established 20-somethings lead with their smaller-run efforts. Whole national prizes are tossed aside to make room in the bylines for pamphlets and salons.

23.

“But I am a novelty But I am a skeleton But I am a handful”

—Ben Ladouceur, “The New Anxieties”

As an example, Crozier and Lane both talked a lot about first collections. First collections are the career milestone that emerging poets are supposed to aim for. That is a simplification, and its loosening grip is apparent in 30 Under 30. Arc editor and 30 Under 30 contributor Ben Ladouceur tweeted this in response to a reviewer’s dismissal of the chapbook aesthetic of Anne Carson’s recent Float: “If you think chapbooks are a lesser art form than trade collections, you legit have my pity.” He expresses here a developing thought that chapbooks aren’t a form of slumming. Perhaps writing the 185th book of Canadian poetry is not an attractive peak achievement for the emerging. This cynicism about mainstream publishing is very millennial and very true to our time. It feels almost rote to call it cynicism. Perhaps it is a kind of optimism.

24.

“The neighbours still like to talk about it.”

—Ellie Sawartzky, “The Boy Next Door”

If we’re talking about debuts and debutantes, should we talk about the qualified poets who aren’t in 30 Under 30? Where is Michelle Brown? Where is Michael Prior? Where is Vincent Colistro? It feels essential, and essentialist, to make a list of unlisted names. It feels like the kind of book criticism that might happen at a party.

25.

“… Here. Let me / slap this poem // like an X-ray onto the snowy screen / and show you where it broke.”

—Dominique Bernier-Cormier, “Switch”

I am a retired wunderkind. My first book was the product of an offhand comment by a teacher to a visiting publisher along the lines of “You should look at Jake’s poems, they’re not bad,” and within a year I had a contract for a quickly-assembled first collection with McClelland & Stewart. I was 22. Every public thing I had ever done before was a product of my own manual labour. I had ran online journals. I had sewn homemade books together with dental floss. I had a sense of myself as an industry. I would have killed to be in 30 Under 30 and panicked at the prospect of a Breathing Fire.

26.

“… I got through war / and peace without remembering a thing”

—Chuqiao Yang, “Nemeiben Road”

That book amounts to my published juvenilia. I don’t dislike my first book, and I don’t disown it, though I never read from it and I don’t own any copies. There are good poems in there. I wrote some of them when I was 17. I feel the same about them as you might feel about what you made when you were 17. They were ragged and earnest and too quick to anger, like their author.

27.

“The ocean will not swallow us”

—Mallory Tater, “Unbendable Light”

None of the poems in 30 Under 30 were written by 17-year-olds, or me. And I’m not comparing them to mine on the level of quality. The anthology’s poems are almost uniformly better. But my experience as someone who might have been published a few years too early is to want to protect these new authors and support their independence. To defend against the structures quickly coming for their voices.

28.

“I am a tiny spaceship. I am waking up beside you in certainty, baby.”

—Ashley Opheim, “Plastic Watermelon”

30 Under 30 will be, to some, a frustratingly insular book, an example of all that’s wrong in CanLit. It’s ageist and cliqueish and disinterested in the broader audience we’re always told is out there. I would argue, from my own small experience, that this is the best possible result. To be a throwaway byproduct of chattering friends, fixable in time and available to academics, but not created primarily for that purpose. Not a catalogue, a yearbook.

29.

“It’s wing night / & the blackout shades are torn”

—Claire Farley, “NU”

The book is not easy to find, and many people who read this essay won’t read it. To that end, I find myself speaking around its poems, and not to them. The poems are there, hinted at in these epigraphs, and they are worth your time. All I’ll say briefly is that, on the strength of the material alone and divorced from the context in these paragraphs, 30 Under 30 is the best read of the three books here considered.

30.

“I hope you enjoyed the show.”

—Trevor Abes, “Cholerophobia”

As an illustration, I’ll say this. If I didn’t know it already, I would not be able to tell which Breathing Fire came first, which was published in 1995 and which in 2004. That’s fine, we’re only talking about a nine-year difference. But I would have no problem choosing 30 Under 30 when asked which of the three books was published this year. Its poems leap between substrates with a grace and dexterity that seems specific to this generation, as I’ve said before. They move from science to art, from high culture to low, and from the beautiful to the grotesque too readily to seem like irony. Their creators deserve the playground that 30 Under 30 provides them. I think these are excellent poems, much better than the work of my own earlier generation.

Jacob McArthur Mooney is thirty-four.

Thanks to Cameron Ray at the Toronto Public Library and Meredith Sharp at the Canada Council for their research help.

i : Toronto Public Library catalogues.

ii : Canada Council Online Submissions Database.

iii : Ibid.

Save